Illuminating the Self Curator Essay

There is a long history of fruitful collaborations between artists and scientists. The exhibition Illuminating the Self shows the strong connection between two fields often assumed to be polar opposites. The process of creating work was driven by in-depth investigation and research, collaboration and experimentation, before final artworks were conceived and developed. The best art that comes from this kind of collaboration, however, does not try to illustrate or simply explain the complex science and engineering. It is a creative response to those discussions and observations, a reaction, or reflection, that aims to cultivate curiosity and provoke further responses from those who encounter it.

Susan Aldworth and Andrew Carnie were invited to make an artistic response to the CANDO research project in 2017. It followed on from earlier discussions with some of the scientists which had resulted in a suite of collaborative prints made in 2015. These works, entitled Enlightened, explored more general ideas around optogenetics and how external manipulation of the brain might alter our sense of self. A prolonged period of research and investigation began in Autumn 2017 when Susan and Andrew began meeting with scientists, clinicians and engineers involved in the CANDO project. The theme of how technological interventions might disturb our sense of self continued to bubble below the surface. Lengthy dialogue followed concerning the neurological aspects of epilepsy, the implementation of the new treatment, how the gene therapy and implant are designed. They spent time studying the complex computer modelling that tests thousands of different scenarios, observed the animal experiments that are essential ahead of human trials, and discussed with legal experts the ethical implications of this kind of technology and what it might mean for all of us.

“There comes a moment during an epileptic fit when my self ceases to be… my brain wipes my sense of self clean, and then my sense of self re-emerges from somewhere else in my brain.”

Max Eilenberg interview with Susan Aldworth

The question of how we construct our sense of self and how it might be changed by the integration of biotechnology within the body has been central to discussions for Illuminating the Self. While we are accustomed to the idea of implants in different parts of our bodies – pins to hold together joints, pacemakers to support the heart – the concept of something controlling parts of our brain appears more difficult to comprehend, more in the realm of science fiction with the potential to elicit fear and suspicion. The brain is the organ responsible for our thoughts, words and actions – the generator and custodian of our memories, our character and personality. Yet the quote from Max Eilenberg suggests that a seizure itself disrupts that sense of self and it needs to be reformed again.

The artworks in Illuminating the Self navigate the scientific and technological aspects of the project alongside the intensely human experience of epilepsy. For Andrew Carnie this has meant focussing on the inner workings of the brain, how they are disrupted during a seizure and how gene therapy and the CANDO implant might modulate the disruption. Susan Aldworth has responded to the inner feelings and experiences of those living with epilepsy. Both artists have explored the unseen qualities of epilepsy and its treatment – questioning what is happening beneath the surface.

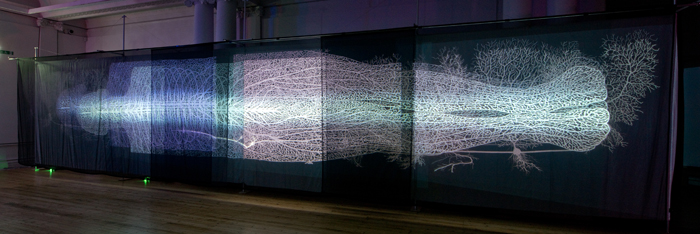

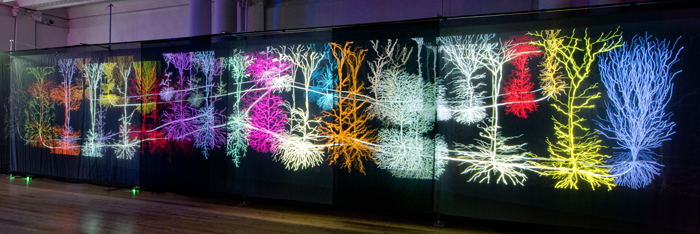

Andrew has made a large-scale new film, Blue Matter, which immerses the visitor in an imagined landscape of the brain. Visual metaphors are created through a combination of drawing and computer animation. Silhouettes of the brain emerge as beautiful and powerful, yet at the same time mysterious and enigmatic. Tree-like forms move and shift mesmerically; jagged lines intermittently cut across them like activity in the brain disrupted by a ‘seizure’. The fragile and delicate forms suggest an idyllic landscape – the brain as Garden of Eden – perfect and untouched. Moving through the largely monochrome film is a hypnotic experience, at times soothing and meditative but with hints of confusion and danger.

Interventions within this landscape allude to the science and raise questions over the dilemma of interfering with such beauty: mistletoe grows amongst the tree branches, the electronic implant descends from the darkness like a road sign in headlights directing a seizure to halt. A series of watchtowers come into view – are they benign or malevolent? The monitoring aspects of the technology is at the heart of its successful application in recognising abnormal brain activity (to deliver treatment) but open to potential interference and misuse. The interventions reflect Andrew’s interest in the application of the technology beyond the CANDO project: “optogenetics research using light to control cells in living tissue may have an impact beyond epilepsy and upon us all”.

The brain is our most complex organ with more than eighty-six billion nerve cells. It is responsible for our thoughts, actions, memories and feelings, yet there remain huge gaps in our understanding of its processes and functions. Blue Matter reflects both the scientific fascination of the brain as well as its intensely individual meaning.

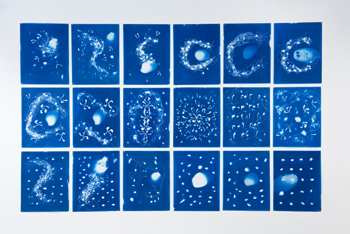

The astonishing intricacy of brain structures and systems is something that Susan Aldworth also explores through a series of cyanotypes. These echo the patterns and shapes of brain activity during an epileptic seizure and again emphasise the beauty of the brain, at once both complex and confusing. The cyanotype process is chosen specifically for its use of light and typical blue colour: as Susan explains, “The cyanotypes are made using ultraviolet light, a process which mirrors the use of light in the optogenetic therapies being developed by the scientists. These prints explore, through pattern, the synchronization that occurs in the brain during an epileptic seizure.”

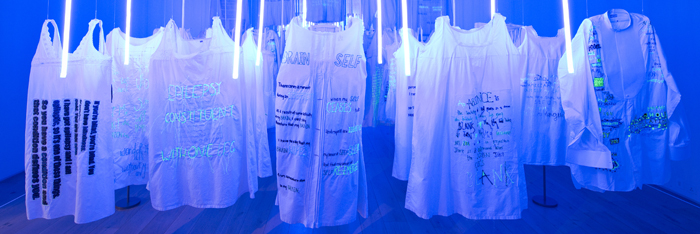

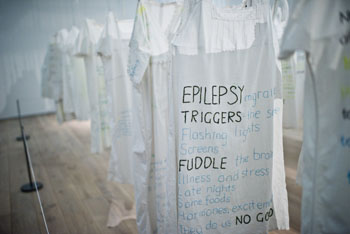

Susan continues the use of ultraviolet light in the dramatic installation, Out of the Blue, which considers what epilepsy means to the people who live with it. How does it feel to experience a seizure? Are there positive dimensions to epilepsy? With the help of The Epilepsy Society, Susan posed these questions directly to people in the UK and beyond who are living with epilepsy. Almost 100 people responded. Their detailed accounts offer powerful and moving insights into their day to day experiences.

“I wake up twice, I regain consciousness a few minutes after a seizure, but it's not really me. It's just the parts of my brain that make me seem awake. My personality, my memories, my emotions - none of that's there.” Willow N interview with Susan Aldworth

The sense that these feelings are often internalised led Susan to the idea of embroidering some of the testimonies onto Victorian underwear – chemises, bloomers and nightdresses, garments that would normally have been concealed beneath an outer layer. The needlework was undertaken by a huge range of individuals including students at the Royal School of Needlework, community sewing groups, other artists and the parents of young people who gave testimonies. They were given threads in ultraviolet yellow, light blue and black and an excerpt from a testimony to embroider on the front with a single word on the back. The scale and form of the stitching was the choice of those sewing and they have been produced in a way that adds further potency to the words. Letters from the word ‘overloading’ are increasingly repeated until they literally hang from the hem.

The embroidered garments have been photographed worn by models, as in a formal portrait, as much an image of the writer of the words as the model themselves. Ambushed, Lonely and Why me? are presented on a model’s back. The words, worn by a person, have heightened significance that alone on a page they might not have.

At the Hatton Gallery, 106 garments are suspended from a complex system of pulleys and motors. Words from the testimonies glow in the natural and ultraviolet light. Periodically they move in a pattern relating to the algorithms of electrical activity in an epileptic brain. The cycle of movement is followed by a period of stillness as balance is restored.

Susan’s series of monotypes, The Portrait Anatomised also examine what it feels like to live with epilepsy. Originally shown at the National Portrait Gallery, these dynamic, abstract portraits combine EEG scans together with photographs, text, etching and medical textbook imagery. Composed of nine separate sections, the dissembled body parts allude to how a person is defined, not just by their medical condition but by the many different facets that shape individuals.

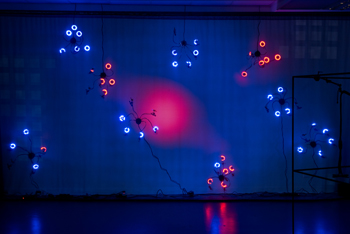

Andrew Carnie explores disruption and balance through a series of sculptures. During an epileptic seizure, the natural rhythms of brain activity are disturbed and there is a catastrophic reduction in its processing power. The gene therapy and brain implant created by the CANDO project seek to restore an equilibrium. In response Andrew has experimented with different objects in changing states. Balloons inflate and deflate, magnets attract and repel, and the lines of light from laser levels are broken and fragmented. In each case the change is triggered by the sound or movement of exhibition visitors. A still state is unsettled before a period of calm returns.

Using programmable USB word fans Andrew has created a second sculptural video work, A Tale of Two. Rings of rotating phrases offer different perspectives on brain implants. The words come from texts on legal, ethical and personal viewpoints as well as Andrew’s own writing and reflect the multifaceted nature of epilepsy, device implantation, optogenetics, and the wider CANDO project.

The exhibitions of Illuminating the Self attempt to give us insight into cutting edge and complex neuroscience, and convey a sense of pioneering research on the brink of breakthrough. They also aim to increase our understanding of what epilepsy is and what it means to live with the condition. Their main concern however remains to encourage visitors to ask their own questions – about the science, the technology, the art, and about themselves.

Lucy Jenkins, curator of Illuminating the Self.